28 Years Later (2025) – The World That Wouldn’t Heal

Some plagues burn out. Others wait in silence, festering beneath the surface, until the world forgets how fragile it is. 28 Years Later (2025) resurrects one of horror’s most terrifying sagas, bringing the rage virus back with a vengeance that is as much psychological as it is visceral. Where 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later painted survival as chaos, this third chapter dares to ask: what does humanity become when survival has lasted too long?

The story begins in a world scarred but not healed. Decades after the original outbreak, survivors live in fractured societies, walled enclaves where order is kept by authoritarian regimes, and the wilderness is left to silence, ruin, and memory. For a generation born after the infection, the rage virus is a legend—a horror story told to keep children inside at night. But when a dormant strain is unleashed, faster, deadlier, and impossible to contain, the legend becomes apocalypse all over again.

At its heart, the film is about legacy. Those who lived through the first waves of terror are haunted by scars and guilt, while the younger generation, reckless and disbelieving, must learn too late that some nightmares never die. Their clash of experience and naivety creates a new kind of tension: not just how to survive the infected, but how to survive each other.

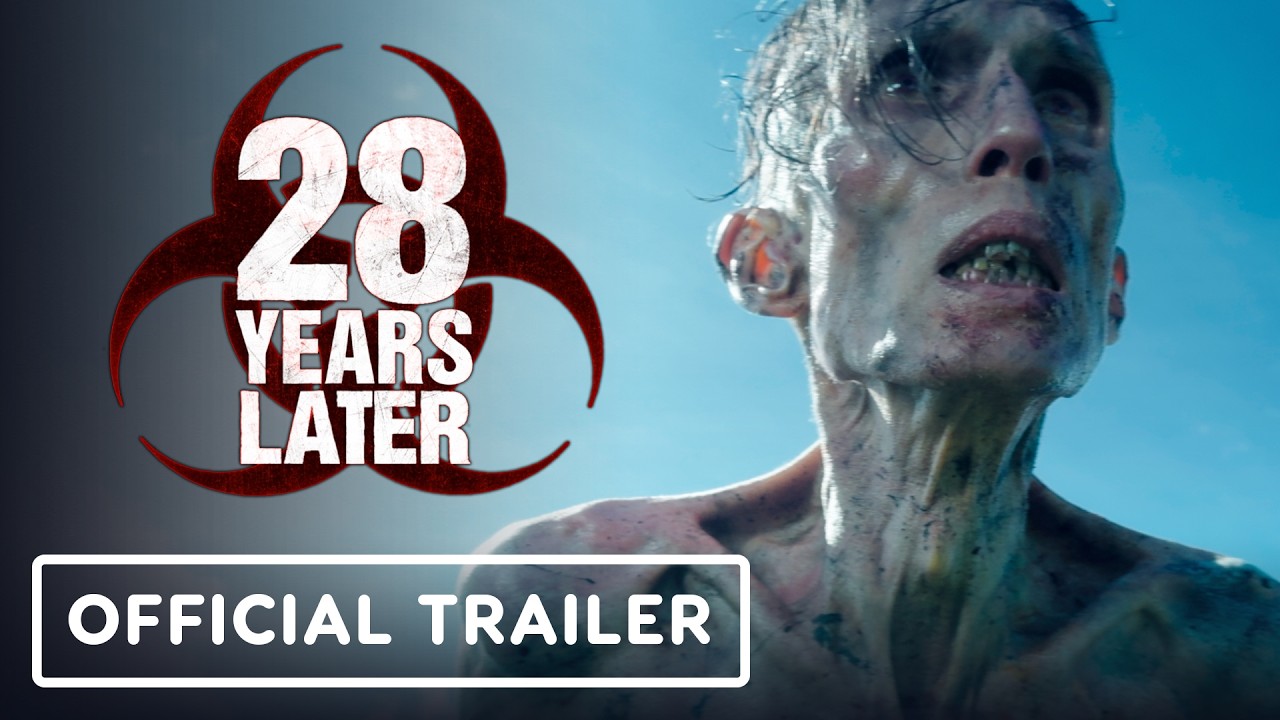

The infected themselves are more terrifying than ever. Faster, more coordinated, and mutated by decades of evolution, they are no longer mindless rage machines but predators honed by survival. Their attacks are staged with unflinching brutality—alleyways drenched in blood, safe zones breached in seconds, and once-sacred refuges transformed into slaughterhouses.

The action is relentless but precise. Large-scale outbreaks explode into chaos, but the film thrives in intimacy: a family trapped in a farmhouse, soldiers turning on one another as trust disintegrates, a single survivor sprinting through an empty city as the silence breaks into a roar. Danny Boyle’s original DNA—gritty realism, handheld urgency—lives on, grounding the horror in something disturbingly possible.

Visually, 28 Years Later blends the emptiness of abandoned cities with the menace of a world reclaiming itself. Nature grows wild, concrete crumbles, and the few bastions of humanity feel fragile, temporary, on the verge of collapse. The cinematography emphasizes isolation, turning every shadow into a threat.

The score is haunting, echoing John Murphy’s iconic “In the House – In a Heartbeat” with new variations. Sparse piano, rising strings, and sudden, violent crescendos carry the audience from dread to explosion, from silence to chaos, embodying the rhythm of terror.

Thematically, the film explores whether survival means resilience or decay. Can a species that has lived through decades of apocalypse find renewal, or are we forever prisoners of fear, building cages that only remind us of what waits outside? The rage virus becomes more than infection—it becomes metaphor for humanity’s own violence, always lurking, always ready to erupt.

Supporting characters carry emotional weight: a hardened leader who survived the first outbreaks but has become ruthless in the name of order, a young rebel who refuses to live in fear, and a mother whose child may hold the key to either salvation or the virus’s final, unstoppable mutation.

By its finale, 28 Years Later delivers devastation. Safe zones fall, families fracture, and survivors face choices more terrifying than the infected themselves. The ending is bleak, ambiguous, and unforgettable—reminding us that in this world, survival is not victory, it is simply delay.

Ultimately, 28 Years Later (2025) is not just a sequel—it is a resurrection of horror at its rawest. Brutal, urgent, and unflinching, it carries forward the legacy of one of the most terrifying franchises in cinema, proving that some nightmares never end. They only wait.

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :