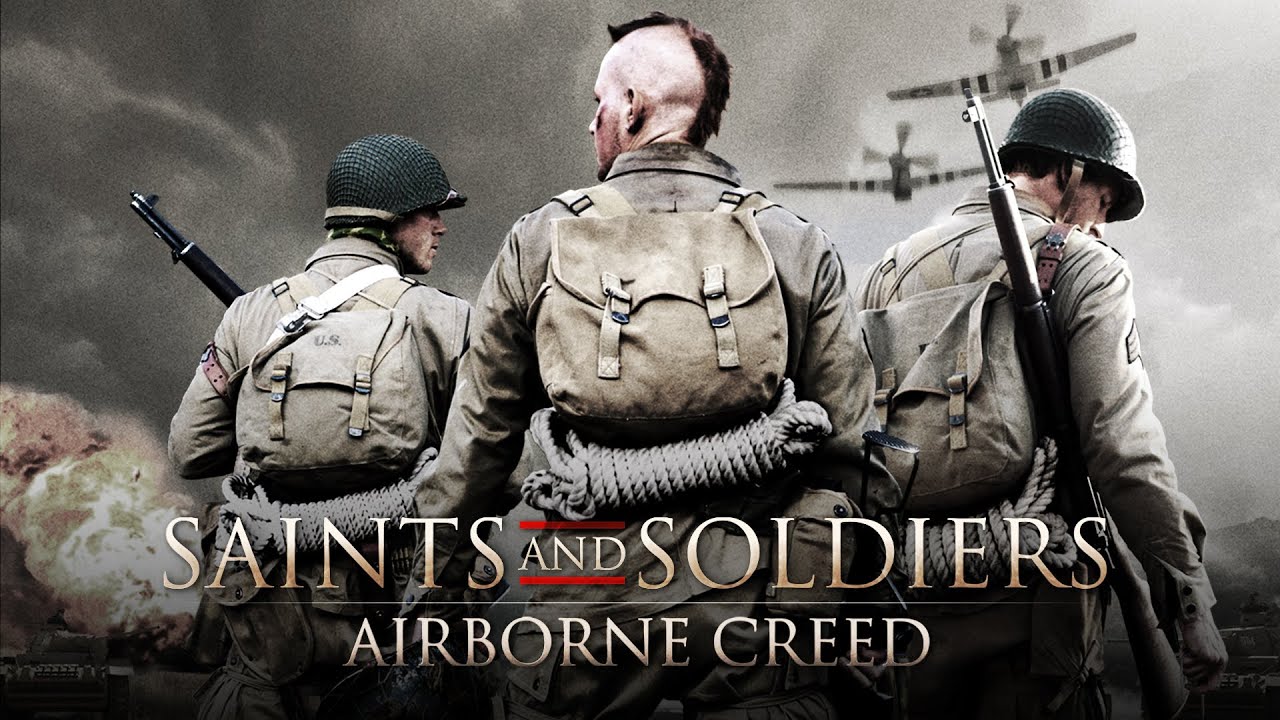

Saints and Soldiers (2003) – Faith in the Fog of War

Some war films thunder with spectacle. Others whisper through silence, snow, and the fragile breath of men who have nothing left but hope. Saints and Soldiers (2003) belongs firmly to the latter—an intimate, haunting World War II drama that strips away grandeur and focuses on survival, morality, and the fragile bonds that form when war reduces men to shadows in the snow.

The story begins in December 1944, during the chaos of the Battle of the Bulge. After a massacre of American POWs by German forces, a small group of survivors escapes into the frozen forests. Alone, outnumbered, and without supplies, they face a brutal winter as dangerous as the enemy itself. With them is a downed British pilot carrying intelligence that could change the course of the war, and so begins their desperate trek through enemy territory.

At its heart, the film is about humanity under siege. These are not superheroes or indestructible soldiers—they are ordinary men, exhausted and terrified, clinging to duty and faith. Among them is Corporal Nathan “Deacon” Greer, a devout man haunted by both his beliefs and the blood on his hands. His quiet struggle becomes the soul of the film, a reminder that war is not just fought on battlefields but within conscience.

The enemy is everywhere and nowhere—patrolling forests, lurking in villages, watching from the shadows. The group’s greatest battles are against hunger, cold, and despair. Every step feels fragile, every silence heavy with the threat of discovery.

The action, when it erupts, is sudden, brutal, and unglamorous. Gunfire cracks across snow, grenades tear through silence, and each skirmish is terrifying not for its scale but for its intimacy. The film captures the truth of combat: confusion, desperation, and the unbearable weight of killing.

Visually, Saints and Soldiers is striking in its simplicity. Snow blankets everything, turning the world into both refuge and grave. The stark landscapes amplify the loneliness of the soldiers, making every shadow and tree feel alive with menace.

The score is understated, relying on somber strings and quiet tones that heighten the melancholy rather than overwhelm it. Silence itself becomes the soundtrack—moments where breath clouds in the air and footsteps crunch softly against the snow.

Thematically, the film is about faith—not just religious faith, though Deacon’s spirituality drives the narrative, but faith in one another, in survival, and in the possibility that humanity can endure even in its darkest hour. It confronts questions of morality in war: how do you reconcile belief in God with the act of killing? How do you hold on to compassion when cruelty surrounds you?

Supporting characters each embody different shades of humanity: cynicism, hope, anger, and loyalty. Their interactions provide warmth in the cold, showing that even in war’s dehumanization, small acts of kindness and trust still matter.

By its conclusion, Saints and Soldiers offers no easy victories. The mission is carried through, but at great cost. The survivors are scarred, broken, yet still breathing—proof that endurance itself can be a kind of triumph.

Ultimately, Saints and Soldiers (2003) is a quiet, powerful war film that speaks less through spectacle and more through silence. It is about men, not armies; conscience, not conquest. Haunting, intimate, and deeply human, it reminds us that even in war, when faith falters, humanity must not.

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :

Related movies :